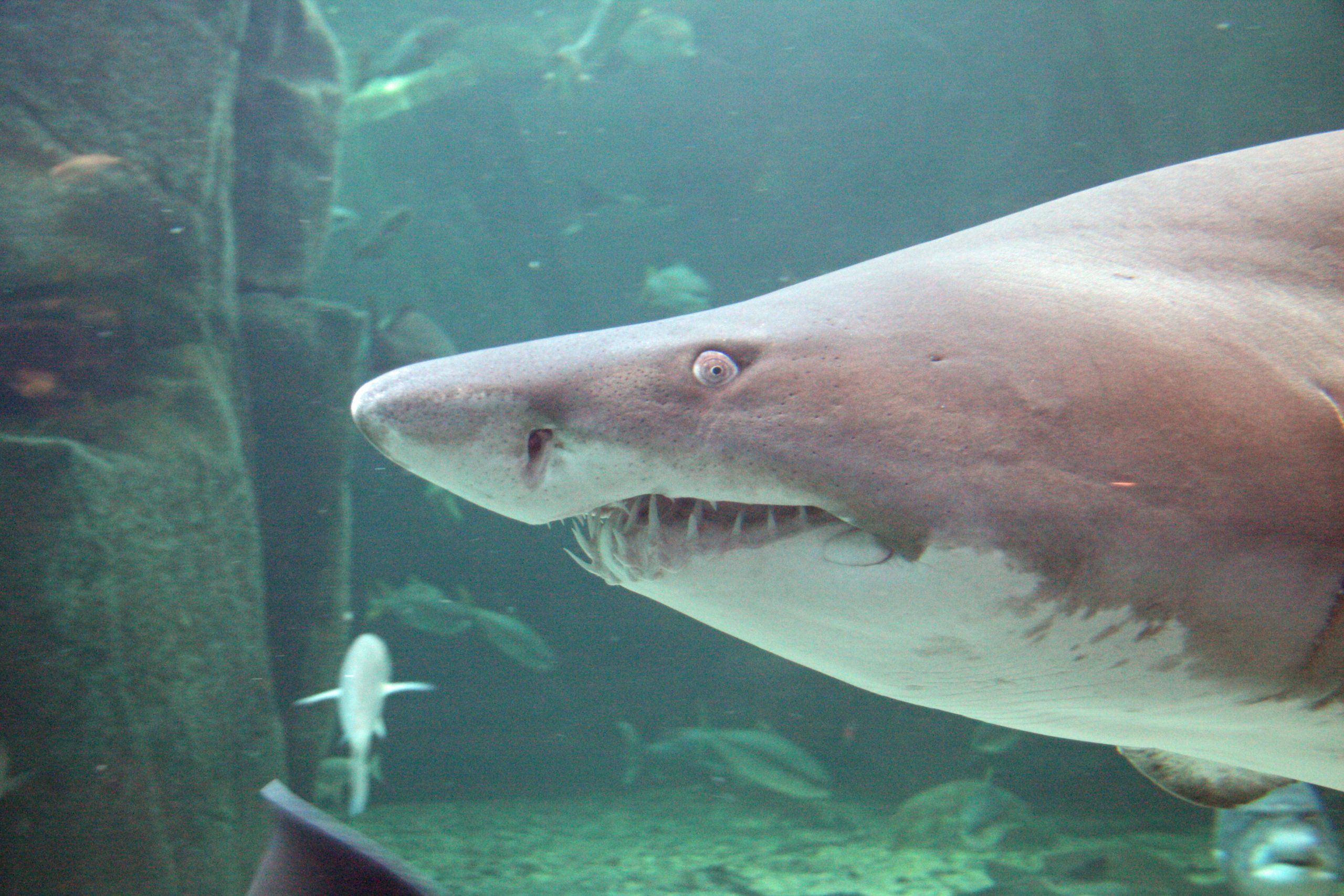

If you’ve ever witnessed a great white shark attack, you know the meaning of the word “relentless.” The giant creature’s dorsal fin traces a circle in the water as it spots a vulnerable victim; the shark makes a first strike, then a second and a third, coolly and methodically; the victim struggles, weakens and finally succumbs to the massive loss of blood. Some victims survive, of course — but for many, once marked for attack, it’s only a matter of time.

It seems that sharks and bankers have a lot in common.

This thought came to me as I read a new report from Moebs with some surprising news: overdraft fees are back. To be precise, as ABCNews.com reported, Moebs found that total revenue from overdraft fees grew from $30.8 billion in June 2011 to $31.5 billion in June 2012, a whopping $700 million increase.

This new surge is surprising, in part, because it comes after four years of major declines — in fact, between 2008 and 2011, overdraft revenue had dropped by $6 billion. But it’s also surprising for another reason: just two years ago, the big banks were mounting a massive and well documented hissy-fit, complaining that a 2010 change by the Federal Reserve in the regulation of overdraft fees would dramatically slash bank revenues, forcing them to eliminate such consumer-friendly features as free checking just to survive.

It’s clear now that the bankers’ plaintive cries of woe were overblown. But what’s even more transparent is the bottom-feeding way the banks have found to turn around their fortunes despite the supposedly devastating blow imposed by the Fed in 2010. Simply put, the formula goes like this: find the weak and squeeze with all your might.

A little background: Until 2010, U.S. banks could automatically sign up customers for “overdraft protection” programs, and they signed them up like there was no tomorrow — a maneuver that brought them tens of billions of dollars in overdraft fees. Consumers (and some members of Congress) rightly complained that these fees were predatory and unfair, noting their disproportionate impact on the poor, the elderly, and minorities, and the perverse techniques the banks used to maximize their gains — including the reordering of transactions from biggest to smallest in order to take as many “bites” as possible.

After a massive tussle, the Federal Reserve imposed a requirement that sounds like a no-brainer: that banks must get customers’ consent before signing them up for a “service” that many never asked for. Consumer groups sought even stronger restrictions, correctly predicting that the changes proposed by the Fed would not be enough to protect consumers from abuse. While praising the extension of the new rule to all debit-card holders, a coalition of consumer advocates noted: “The rule addresses neither the high cost of the overdraft fee relative to the overdraft amount nor the frequency with which overdraft fees may be charged. It also does not address manipulation of posting order to maximize overdraft fees.”

As it turned out, the failure by the Fed to address these demands was decisive in leading to the current situation — though you wouldn’t have known at the time that the banks had anything to be happy about. Discussing the new regulations in a 2010 letter to shareholders, Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said that “we estimate these changes will reduce our after-tax income by approximately $500 million annually.”

We now know that things worked out differently. As economist Michael Moebs, CEO of Moebs Services, puts it: “Despite regulation and legislation … consumers’ use of overdrafts shows no indication of going away.” Moebs says the latest increase is fueled partly “by increases in consumer demand.” But Moebs own report shows that this isn’t the case. In reality, the total number of overdraft fee charges actually dropped by 1.4% last year. The increase in revenue happened, instead, because banks and credit unions continued to jack up fees, with the average cost per overdraft rising by 3.6%.

What the report really shows is exactly what federal regulators and consumer advocates have predicted for years: High overdraft fees are pushing millions of Americans out of the banking system entirely and into things like payday loans, which have significantly higher cost and significantly lower protection for consumers. In fact, according to an FDIC report, overdraft fees are the leading cause of involuntary bank account closures. And while it’s scandalous enough to see how much money the banks are pulling in through these fees, the bigger scandal is where this money is coming from. Then and now, these fees have fallen disproportionately on the people least able to pay them: seniors, the young, minorities, the disabled, and military families. This is intolerable. It must be stopped.

The Fed’s 2010 opt-in rule was a good first step. But banks have figured out ways around it to keep their pipeline of easy money flowing, with no regard for how much it hurts consumers — or which consumers get hurt. Here are some suggestions for how federal regulators can create more protection for consumers and staunch the flow.

- Ban all overdraft fees on debit card and ATM transactions. These transactions can easily be declined at the point of purchase, at no cost to the consumer. The only reason for doing it the way we do it now is to shovel more money into the banks’ coffers.

- Lower fees, and make them proportional to the amounts involved. The average large bank charges $35 per overdraft. That’s ridiculous. It simply does not cost banks $35 to extend a short-term loan to a customer — especially since most transactions are for extremely small amounts. Rather than being a profit center for banks, overdraft fees should be proportional to banks’ actual costs, just as the FDIC requires of penalty fees on credit cards.

- Overdrafts by paper check cannot be automatically declined. If a customer incurs six such overdraft fees in 12 months, they should be given the option of paying off those short-term loans (which is what an overdraft fee is) in installments.

- Ban payment chicanery. Many banks and credit unions have stopped processing purchases and ATM withdrawals as the transactions happen. Instead, they post the biggest transactions first, hoping to drive customers over the limit. This must end. Customers have the right to expect that their transactions are being processed as they are made, and that they are not being forced into paying high fees by bank trickery.

- If banks want to extend credit by way of overdraft fees, they need to tell customers exactly what the APR is on each short-term loan.

Predation is as old as the food chain, and it is nature’s way to favor the strong. But we’re building a civilization, not a Darwinian theme park. For our nation to move forward, we must broaden opportunity and strengthen each individual’s prospects of success. Above all, we must not allow the most vulnerable members of our society to be tricked and exploited to fatten the sharks circling among us. Success is a good thing, but not at the price of our soul. We can do better than that.

Originally published on Credit.com