The breach at Home Depot is only the most recent in a torrent of high-profile data compromises. Data and identity-related crimes are at record levels. Consumers are in uncharted territory, which raises a question: Is it time to do for data breaches and cybersecurity what the nutritional label did for food? I believe we need a Data Breach Disclosure Box, and that it can be a powerful consumer information and education tool.

Once a cost of doing business, today data breaches in the best-case scenario can sap a company’s bottom line, and at their worst represent an extinction-level event. The real-world effects for consumers can be catastrophic. Because there is a patchwork of state and federal laws related to data security—some good, some bad, all indecipherable—and none that work together, it’s impossible to know just how safe your personally identifiable information is, and has been, at the places where you shop and the companies and professional organizations with which you do business.

Data security, identity-related consumer issues and privacy are all areas screaming for big-picture solutions. This is a situation in search of a paradigm shift—one that produces tools which enable consumers to make informed choices.

There is a precedent that could serve as a template. Passed in 1988, but not implemented until 2000, you may recognize its name—it’s called the Schumer Box. This is the law that put the fine print of credit terms and conditions in your face—bigger, bolder and easier to understand. You see it all the time featured in those countless pleas for your credit business that land in your email and your mailbox.

The Schumer Box is simple. It requires financial services companies to provide certain information to the consumer when making a pitch for their business—information like long-term rates, the annual percentage rate for purchases and the cost of financing—and that the information be displayed in a standardized fashion. The Schumer Box is to credit cards what the nutritional label is to food.

A Concise Disclosure for Breaches

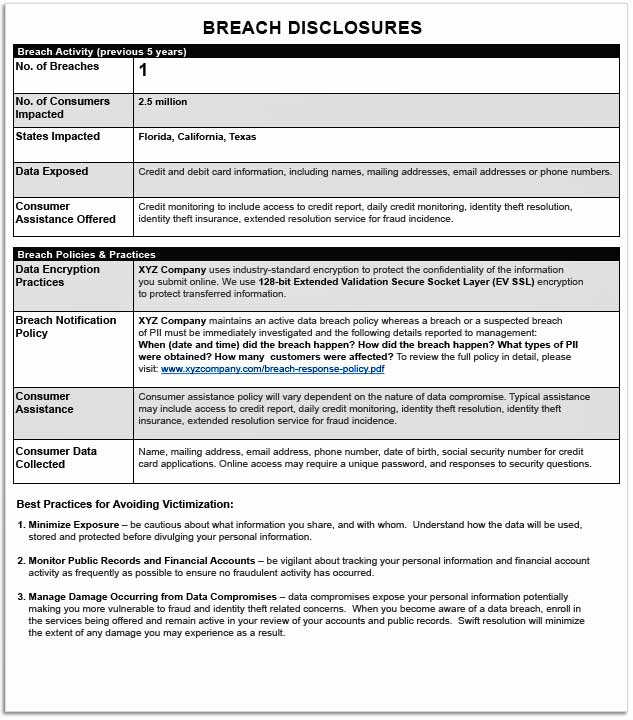

The Breach Disclosure Box that I am proposing would need to be simple, too. While I believe it is important to create a system that informs consumers about breaches, bear in mind that all breaches are not alike. There are breaches where the only piece of compromised information was an easily changed credit card number for which the consumer had zero liability. Then there are breaches involving Social Security numbers, detailed banking data or personal health information. These are very different situations. But they all share one thing in common: Something about you is “out there” and can be used by a criminal to commit either a crime against you or in your name.

The “solution” — regardless a breach’s severity — is the same. I place “solution” in scare quotes, because it’s a misnomer to talk about solutions and identity-related crime in the same breath. There is no solution to the pandemic, only containment strategies and best practices.

The “solution” — regardless a breach’s severity — is the same. I place “solution” in scare quotes, because it’s a misnomer to talk about solutions and identity-related crime in the same breath. There is no solution to the pandemic, only containment strategies and best practices.

The Breach Disclosure Box would be a crucial part of data-related best practices at the consumer level where it’s all about the 3 M’s: Minimizing your exposure, monitoring your public records and financial accounts, and managing any damage that occurs from data compromises. Best practices can mean the difference between having a bad day and being financially ruined (or worse), and knowledge of a company’s data security track record can help consumers be better informed about the risks they’re taking – and ultimately to decide if the risk is worth it.

The Breach Disclosure Box would also be a catalyst for companies to step up their game on data security as well as design and implementation of a breach preparedness plan that promotes an urgent, transparent and empathetic response to any compromise of consumer and employee data.

While the following list of Breach Box disclosures could be longer or shorter, the basic idea of a Breach Disclosure Box is essential to consumer safety in this ever-changing and crafty world of data-related crime and data breaches

- How many times has this company been breached within the past five years?

- If yes, what kind(s) of information was exposed?

- Does this company encrypt all consumer and employee data?

- Does this company have a breach notification policy?

- What did the company offer affected consumers?

- What type(s) of information are customers obligated, or not obligated to provide?

- Best practices for avoiding victimization (The 3 M’s)

The contents of the Data Breach Disclosure Box would ultimately have to be framed by lawmakers and interested parties intent on limiting the amount of ink spilled (or bytes used) to comply with whatever the legislation looks like when it leaves committee; but this bipartisan issue goes way beyond Blue State-Red State politics. When it comes to data-related crime, we’re all in the same state—a state of emergency.