When it comes to conspiracy theories, a general sense of paranoia is essential. For the weirdness to thrive–human trafficking rings run out of pizza parlors, falsified mass shootings, and alien reptilian overlords–there needs to be an ornate architecture of conspiracy to conceal such horrors from all but a few select online forums, radio shows, and of course the occasional Congressperson.

Mass delusion that fosters viral paranoia might be something we can harness to promote better cybersecurity. The bottom line in that anyone with an internet-connected device should act as if there’s a malevolent threat actor just around every corner, because there very often is.

Your email is a constant target for phishing campaigns, your workplace network is almost certainly being scanned for vulnerabilities, and your apps are constantly compiling piles of data about your every move.

Keeping this in mind, a sense of paranoia can actually be a good thing, but it can go too far and backfire.

Case in point: I recently published an article new vulnerabilities announced by Apple. The details don’t matter. They announced a few fairly urgent security holes in their products, issued a patch, and suggested that anyone who owned devices affected by the problems download the patch as soon as possible.

The response on social media was not what I expected.

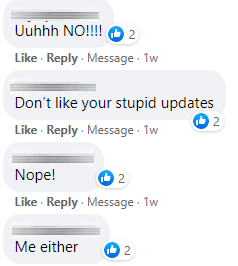

“Uuhhh NO!!!!” wrote one person.

“Nope!” wrote another.

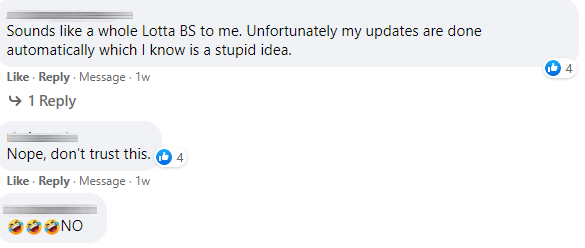

“Sounds like a whole Lotta BS to me. Unfortunately my updates are done automatically which I know is a stupid idea,” wrote someone else, who was kindly informed by another person that automatic updates could be disabled. (Note: this is a bad idea.)

There were only eighteen comments on my Facebook post about the update. Seventeen made it known that they would not be taking my advice.

Obviously this is anecdotal. Most likely, the majority of people who read the article or saw the news elsewhere downloaded the update and went on about their lives.

While only one of the comments on my article specifically mentioned Parler, the sentiment seems clear: In the wake of MAGA and QAnon-friendly accounts being deplatformed on social media and online, the political Right’s distrust in tech companies has experienced a marked increase.

Regardless of the visibility of trolls, it suggests that paranoia may present a hurdle for cybersecurity and the adoption of sound data hygiene.

The primary hurdles when it comes to security patches are laziness or unfamiliarity with the way updates work. Now it seems in the wake of QAnon that people may not be taking basic steps to protect themselves because they don’t trust the source, which ironically makes them a perfect target for hackers and scammers.

The thousands of flat-earthers out there underscore the grim reality that overcoming vague and irrational suspicions is no easy feat. As our media and culture become increasingly fractured and conspiracy theories go mainstream, the resulting paranoia may very well increase our collective attackable surface.

Takeaways:

- Tech companies such as Apple and Google release urgent patches when new vulnerabilities are found in their software. Applying them as quickly as possible is one of the best ways to avoid getting hacked.

- Hackers exploit conflict and thrive in a distrustful environment. The 2020 election and Capitol riots are no exception.

- Publicly announcing your refusal to apply security patches puts a target on your back for hackers and scammers.