What seemed like a farfetched scenario out of Hollywood four years ago is now yet another reality that security experts have been warning about.

What seemed like a farfetched scenario out of Hollywood four years ago is now yet another reality that security experts have been warning about.

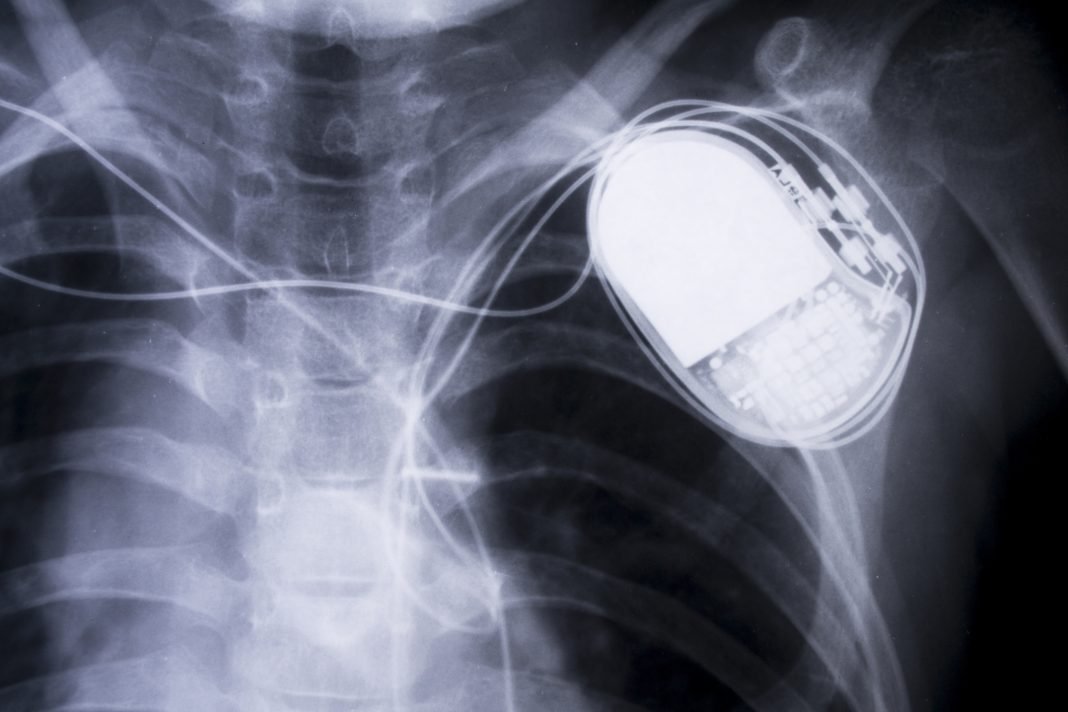

In the screen version, the U.S. vice president is assassinated on the TV show “Homeland” after a hacker takes control of his pacemaker and stops his heart—making it look like a heart attack.

In real life, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently released a safety warning that St. Jude Medical implantable cardiac devices and their remote transmitters contain security vulnerabilities. An unauthorized party could use the vulnerabilities to “modify programming commands” on the device that could result in rapid battery draining or “administration of inappropriate pacing or shocks.”

Coincidentally, the warning came on the heels of an FDA document addressing this very issue: At the end of December, the agency released its guidance for the post-market management of medical device cybersecurity.

The guidance is similar to a previously issued one for premarket design and development. Both are nonbinding.

The FDA can take action against products that violate the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which could include devices that pose serious injury or death risks and lack remediation. Outside of that, it’s unclear what, if anything, the FDA would do about lower-level risks that are not being mitigated.

Enforcement or not, there’s plenty of skepticism about the influence the document will have on device manufacturers. Security experts call it a good first step—emphasis on “first.”

But they are not convinced that the guidance will motivate the industry to make medical devices more secure.

“Absent of serious crises or patient deaths, I’m not optimistic that this document will get the attention of many companies building medical devices,” says John Dickson, a principal with the security firm Denim Group Ltd., and who formerly served at the Air Force Information Warfare Center.

The guidance “emphasizes that manufacturers should monitor, identify and address cybersecurity vulnerabilities and exploits as part of their post-market management of medical devices.”

Among other things, the FDA recommends that manufacturers:

- Follow the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Security, which is widely used in many industries

- Implement a risk-management program for identifying and assessing vulnerabilities

- Act on information about vulnerabilities and deploy patches quickly.

A big problem to crack

Dickson says that the sheer number of devices in circulation—potentially millions, registered to some 6,500 to 7,000 manufacturers—creates a major problem.

“Most of the medical device companies are just trying to get the capability to work well—and here comes (a problem) they really didn’t consider before,” he says.

The embedded sensors and devices were designed for a long lifespan and, in many cases, not intended to be upgraded.

“If those devices cannot receive software updates at some time in their lifespan, they will be vulnerable, so the risk is enormous,” says Hamilton Turner, chief technology officer at mobile-security vendor OptioLabs.

The industry has been slow to react.

Ashton Mozano, chief technology officer at Circadence, a “next-generation” provider of cybersecurity training, says that some of the device vulnerabilities have been known for as long as a decade. But the response has not been like in airline or automotive safety, where “there’s a whole community that gets up in arms” when there’s a faulty or dangerous product.

“We don’t really see that in cyberspace yet. The medical device industry, as well as the IoT realm, have been essentially isolated from that level of widespread global scrutiny,” Mozano says.

The FDA began warning about the problem a few years ago. The guidance certainly indicates the agency’s interest in cybersecurity is growing. Unfortunately, the FDA may not be in the best position to address the problem.

“They’re not in the best situation to have the knowledge and skill set … to mandate regulations for the cyber industry,” Mozano says. “They don’t want to overregulate.”

Plenty of gaps to be filled

The FDA defines patient harm as physical injury, damage to health, or death. Other types of harm—such as loss of personal health information—is excluded from the FDA’s scope.

Turner thinks that’s an oversight. He says that data taken from a device can sometimes include information about the operating environment, including secure Wi-Fi access that could be used to access the network and cause patient harm.

“Ignoring loss of data in a security context can lead to some very serious repercussions,” he says.

Long-term execution of the guidance also is questionable. Mozano says there needs to be “a clear assignment of roles and responsibilities throughout the entire vertical and horizontal supply chain.” And, there needs to be better leadership and a more systematic, step-by-step implementation, he says.

The FDA could take a page from the automotive industry, where rankings by third-party evaluators such as JD Powers influence buying decisions. This would not only motivate manufacturers to protect their reputation, but also put some of the power into the hands of the users.

“This could be more effective than having draconian regulations,” Mozano says.

The industry sentiment seems to be that scenarios à la TV’s “Homeland” are still farfetched. Even the Department of Homeland Security said the vulnerability in St. Jude’s devices would have required “an attacker with high skill.”

But Dickson emphasizes that what was science fiction as recently as two years ago is now becoming a major problem. After all, not too long ago “people said political campaigns were too sophisticated to hack.”

“Given the widespread and ubiquitous nature of medical devices, the fact that a more sophisticated attacker could do this means it will happen at some point,” he says. “As the sophistication goes down the chain, there’ll be more automation to do it. At this point, nobody has figured out how to automatically attack, but that will happen.”

This article originally appeared on ThirdCertainty.com and was written by Rodika Tollefson.